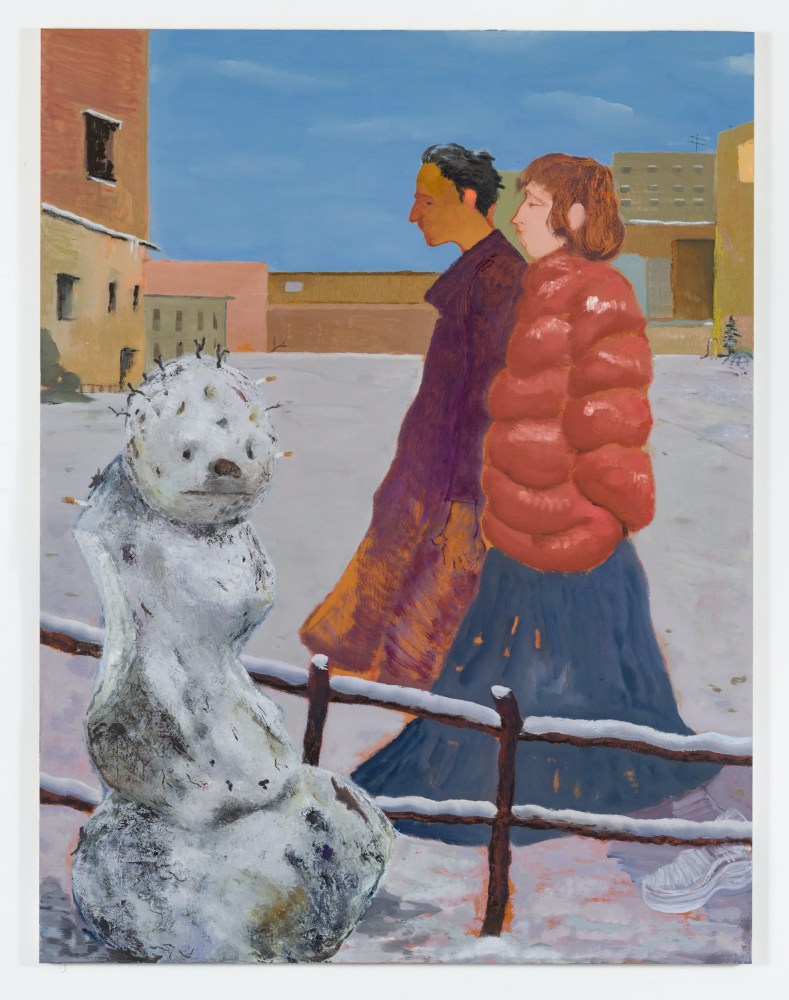

Sanya Kantarovsky, Baba, 2019. Oil and watercolor on canvas. © Sanya Kantarovsky.

Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London, and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

Timeless forms and tropes able to withstand sharp aesthetic shifts in context and representation

What makes a story compelling without being told? This question lingered with me after seeing Sanya Kantarovsky’s exhibition On Them. His paintings, drawings, and prints have long shared an eerie likeness to novel illustration, and give the impression of Russian novels—though only vaguely. Kantarovsky was born and raised, in part, in a Jewish household in Moscow and read the works of Mikhail Bulgakov, Franz Kafka, and other Eastern European authors at a very early age, which left a significant impression on him.1 Each of his paintings could represent a complex scene from any of Dostoevsky’s stories of moral degeneration, desire, comedy, idiocy, and loss, while also being reminiscent of Soviet-era Yiddish stories of horror and strangeness by Peretz Markish or Isaac Bashevis Singer.

But Kantarovsky’s work is striking and eclectic in style. He makes such frequent and simultaneous reference to disparate periods in the history of European painting that one hardly needs to think beyond the sense of déjà vu with regard to literature. Additionally, he finds subtle (and not so subtle) ways to interject the present into his work. We find this in Baba (all works 2019) and High and Low, with references to contemporary fashion, a dirty cigarette-ridden snowman, and a bong. The impression one comes away with, in all his work, is that many forms and tropes are timeless and therefore able to withstand sharp aesthetic shifts in context and representation.

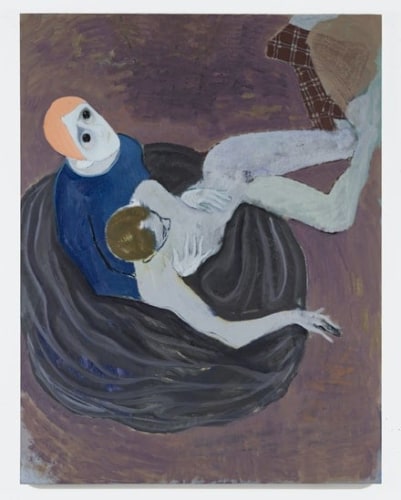

Sanya Kantarovsky, Fracture, 2019. Oil and watercolor on canvas.

© Sanya Kantarovsky. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London, and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

In On Them we find a repetition of scene that betrays conventional illustration and storytelling. Meta-narratives about narrative are—along with many other contemporary painters—essential to Kantarovsky’s approach. Three paintings stand out as a group in this regard: Fracture, Beach, and Needles. Each scene depicts a figure carrying or supporting another—one that is respectively frail, helpless, or dead. Deep, somber blues and twilight grays give each the immediate impression of the sadness of Picasso’s Blue Period. The eyes of the crouching figure in Fracture, staring woefully, longingly, up to heaven, resemble the characteristically glossy eyes of El Greco’s figures, and the limp corpse in her arms the impression of Egon Schiele’s gaunt, gray bodies. Another corpse-like figure in Needles lies in profile, covered in fabric patterned with syringes, wiry IVs stick out from her arms. She is supported by another figure from behind. In Beach a ghostly woman draped in white is carried to the ocean. She gestures with her hand toward the water and a dog follows them. Represented here is less a specific narrative than a story told through repetition. A vaguely Christ-like figure, supported by a loved one: old, oddly familiar tragedies of senseless loss are abstracted, told without names, and from different angles.

Read full article at brooklynrail.org