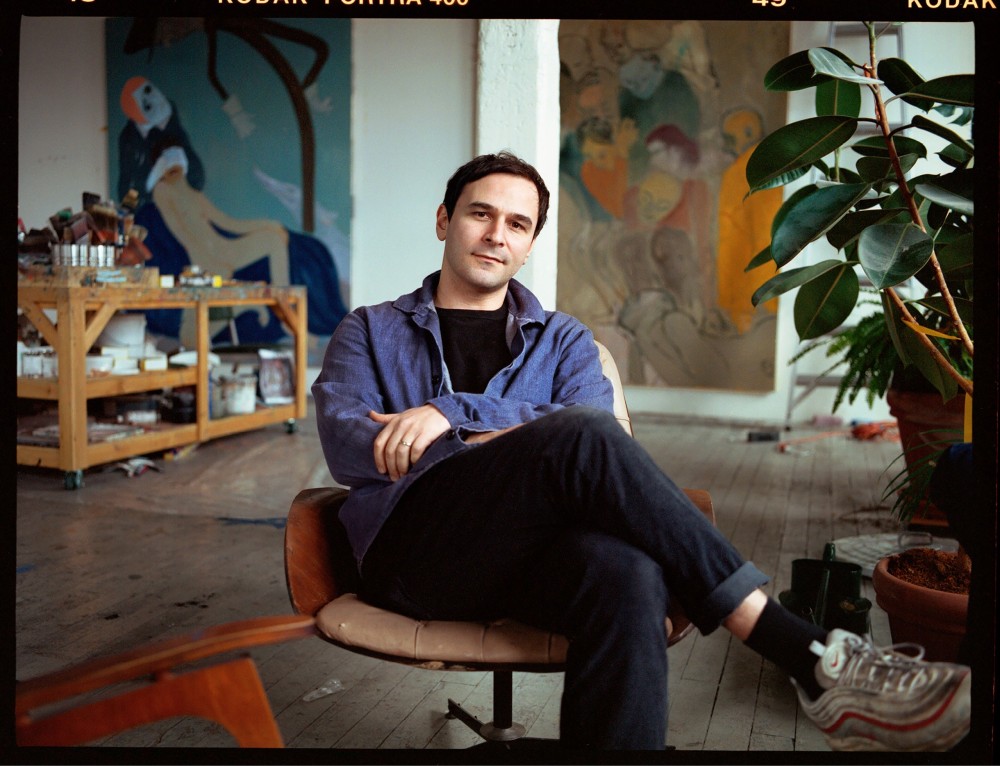

Sanya Kantarovsky. Photographed by Josh Olins

Sanya Kantarovsky has just finished a painting. When I visit him in his Brooklyn studio, he tells me that the night before, he had been struggling with a piece he’d been working on for two weeks, and then, all of a sudden, around 4:00 a.m., he had a breakthrough. He painted over it and made a new one. It’s called Bud 5, and it shows a distressed man—one oversize hand held out in a “stop” gesture, the other pointing a pistol at the ceiling. “Bud” is R. Budd Dwyer, Pennsylvania’s state treasurer in the 1980s, who was convicted on bribery charges and shot himself in the mouth at a televised news conference. Kantarovsky, 37, was too young to be aware of the news at the time, but a friend later told him about the incident, and he watched the suicide on YouTube. His painting is based on a photograph of Budd that became famous in the aftermath of this death, in which he is reaching out to calm the bystanders who panicked when he pulled out the gun. “I love the contradiction of this guarding, tender, safekeeping gesture,” he says, “while he wields an instrument of death.”

Allergies (What Little Else I Remember of You), 2014. Oil, oil stick, pastel, watercolor on canvas, 75 x 60 inches.

Photo: Dawn Blackman. Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London, and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.

Bud 5 is not in the show that opened this spring at New York’s Luhring Augustine—Kantarovsky’s first with the gallery—but it is indicative of the kind of contradictions at the center of his recent work. In one painting, a group of adults looks down on a naked, headless baby who is dancing and playing the accordion. “They’re mesmerized by and indifferent to this decapitated future,” Kantarovsky says. In another, called On Them (also the title of the show), a man with a ski-jump nose, wearing an orange shirt and standing in a pool of water, looks skyward as he twists the neck of a ghostly victim.

Kantarovsky, black-haired and soft-spoken, is a storyteller whose stories resonate with dark humor and unearthly situations. A wild patchwork of influences runs through his work—surrealism and symbolism; Gauguin, Chagall, Ensor, Matisse, and Blue Period Picasso; also folktales and cartoons and children’s books; figuration and abstraction. The offbeat comedy of his work does not resemble what you find in Roy Lichtenstein and Philip Guston, or in Carroll Dunham, George Condo, Lisa Yuskavage, or any number of other contemporary artists. Kantarovsky’s humor doesn’t make you laugh out loud. It’s rooted in Russian and Eastern European aesthetics, the corrosive, embarrassing, upside-down, melancholy strain that you find in Kafka, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (Kantarovsky’s favorite novel), and, for that matter, in the early–twentieth century Soviet satirical magazine Krokodil. “Humor is central to my work,” he says. (The title of the only monograph on his work so far is No Joke.) “Art has never been about morality or about the pure and clean and correct. It’s always been about the grime and pain and totally unfair contradictions of being alive—and humor, very much so, is a kind of pressure valve.”

Read full article at vogue.com